FORT WORTH — Jamal Cyrus works in layers. Layers of materials and associations.

The Houston-born and -based artist, educated at the universities of Houston and Pennsylvania, works in a vast array of media, in two and three dimensions, and sometimes in sound. But the show of his recent works at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth lives up to its “Focus” label.

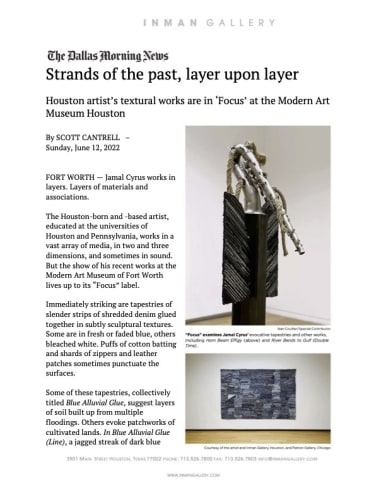

Immediately striking are tapestries of slender strips of shredded denim glued together in subtly sculptural textures. Some are in fresh or faded blue, others bleached white. Puffs of cotton batting and shards of zippers and leather patches sometimes punctuate the surfaces.

Some of these tapestries, collectively titled Blue Alluvial Glue, suggest layers of soil built up from multiple floodings. Others evoke patchworks of cultivated lands. In Blue Alluvial Glue (Line), a jagged streak of dark blue across a white background suggests a river flowing through. But these works, notably Blue Alluvial Glue (Shape), also can be read purely as textured abstraction.

Texas rivers and the cultures that have grown up along them have been inspirations for Cyrus.

“Most of the historical material I deal with relates to what would be considered the Black radical tradition,” he explains in a handout. “I’m interested in the ideas and strategies Black folks develop to get through very dire social circumstances.”

By the 1820s, white settlers were cultivating these soils for cotton and other crops. The work was largely done by Black slaves — 182,566 were counted in Texas in the 1860 census — and farm workers’ lives scarcely improved after emancipation.

As with the Quilts of Gee’s Bend, patched together by poor Black women in isolated Alabama communities, these shredded jeans evoke hardscrabble past lives. But jeans, even tattered, are still worn in all socio-economic strata, an enduringly shared experience.

Multiple strands of Black Texas music are also woven through Cyrus’ works. A lifelong music lover, Cyrus cites the legacy of Coutchman-born Blind Lemon Jefferson, the father of Texas blues, and jazz greats Ornette Coleman and Julius Hemphill, both Fort Worth natives. The zigzags of Common Tongue, perhaps suggesting jazzy syncopations, are topped with a crisp army of black piano sharp keys.

More explicitly musical, Horn Beam Effigy is a totemic construction topped by an inverted saxophone, the instrument of Jefferson, Coleman. and Hemphill. With heavy ropes spewing out of its tone holes — make of that what you will — it caps an upright rail with Picasso-ish wings. The base is a bed of gravel framed by old railroad ties, the underlay of escapes from rural and provincial Texas. Port of Call whimsically attaches a conch shell — a different medium for listening — to a microphone stand and cable.

Music half-remembered is evoked in two works of graphite powder on sepia-colored paper, both titled Rite_1-Percussion Ballad. Fading music ledger lines are crisscrossed with strips of ghostly dots suggesting some otherworldly musical notation.

Rooted in earth, echoing lost music, Cyrus’ layered art is visually engaging and deeply humane. Let’s hope we see more of it.